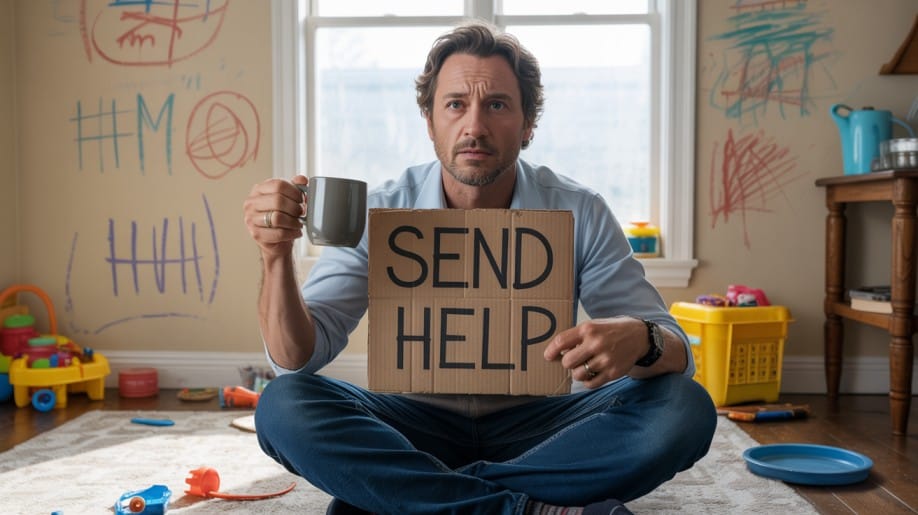

Acting Out: When “No” Means War and You’re the Enemy

Quick Summary:

This blog helps dads decode acting out for what it really is: a struggle to communicate, not misbehaviour. It clarifies the line between tantrums and deeper patterns, and reminds you: your child isn’t giving you a hard time. They’re having one.

What Your Kid Can’t Say, They’ll Show You Through Acting Out

Tic-tac. Tic-tac. Tic…BOOM.

Some days feel like you’re raising a living time bomb.

And the explosions? They come from the most unpredictable places:

The bathwater is too wet.

You dared to swallow the banana they gave you.

You refused to let them lick the electrical outlet.

Suddenly, you’re in a full-blown crisis over a broken cracker or the wrong sippy cup.

If you’re a dad stuck wondering what just happened, you’re in good company.

This isn’t mischief. It’s communication.

Let’s unpack the meaning behind the outbursts and how to stay steady when everything else is spiralling.

What Does “Acting Out” Actually Mean?

“Acting out” is what we say when our kids go full gremlin. But psychologically, it means this: Using behaviour to express emotions they don’t yet have language for.

Honestly, it makes me wish toddlers came equipped with subtitles.

But since they don’t, we get:

Instead of “I’m anxious,” they throw a block.

Instead of “I’m frustrated,” they scream because the banana split in half.

Acting out isn’t manipulation. It’s a loud, messy version of I need help.

It’s their way of saying I’m not okay using the tools they do have. Very efficient tools, by the way.

Why Kids Act Out?

They’re not plotting against you. Their brains are still under construction.

Specifically, the prefrontal cortex (the command centre for self-control and emotional regulation) isn’t finished growing until their mid-20s.

(Which also explains why so many teenagers treat common sense like optional suggestions.)

One key culprit? Impulsive behaviour.

Not bad choices, just brains sprinting before they’ve learned how to brake.

- A study of school-age kids showed that impulse control strengthens in stages, with big leaps between grades 4 and 5, in line with frontal lobe development. PubMed.

- Research using near-infrared spectroscopy shows that executive functions like inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility in young children are closely tied to the development of the lateral prefrontal cortex, underscoring that poor impulse control reflects brain immaturity PMC.

Examples of impulsive behaviour:

- Smacking a sibling mid-laugh

- Blowing out someone else’s birthday candle

- Running toward traffic without looking

- Screaming in a quiet room

None of these are moral failures. They’re development in action. Kids are driven by emotion, curiosity, or sensory need, not malice.

Tantrums vs. Acting Out: Which Bomb Just Went Off?

Tantrums and acting out overlap, but they’re not the same beast.

The spark? Often tiny and irrational:

- The blue ball is too blue

- They’re not allowed to drink toilet water

- Or worse: they just learned they can’t microwave the puppy

Their brains glitch. Their body reacts. Language? Offline.

In 2003, Potegal & Davidson broke tantrums into two phases:

Anger Phase: kicking, screaming, throwing

Distress Phase: whining, sobbing, collapsing

They found that these behaviours followed a predictable arc, often starting in rage and melting into sadness. Most tantrums, they observed, peak quickly and taper off in under five minutes PubMed.

Acting out, though? It’s less about the moment, more about the message.

It shows up as defiance, boundary-testing, shutting down — behaviours that return again and again, often pointing to unmet emotional needs.

Here’s the shortcut:

- Tantrum = momentary meltdown

- Acting out = a message in behavioural form

Tantrums usually pass on their own. Acting out often needs you to decode the root cause.

Is Acting Out Normal? (And When Should I Worry?)

Yes, acting out is normal. In fact, if you have a toddler between 1 and 4 and haven’t experienced it in public, are you even parenting?

But not all acting out is equal. When it becomes chronic, disconnected from obvious triggers, or doesn’t improve with consistent parenting, it might point to something deeper.

Watch for:

- Persistent aggression toward others or self

- Destruction of property

- Chronic defiance

- Social withdrawal or regression (like losing previously gained skills)

Some kids who continue to show disruptive behaviour beyond early childhood may be exhibiting signs of Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) or Conduct Disorder (CD). PubMed.

The good news?

Pediatricians and child therapists are trained to decode these behaviours and help you respond with the right tools and the right intention.

What To Do When Your Kid Acts Out?

First off, you’re not a bad dad for feeling overwhelmed. Acting out can push every button you’ve got.

Instead of punishment-first, try this:

- Stay calm (or fake it until your nervous system catches up)

- Name the feeling: “You’re mad because the tower you just broke is broken. I get it. That sucks.”

- Offer a do-over: “Want to try that again with your words instead of your fists?”

- Breathe together: 4 in, 4 hold, 4 out.

If you’d like to delve a little deeper, consider reading this article about gentle parenting.

Why These Steps Work (Backed by Science)

Ever heard of PCIT? That’s short for Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. And no, it’s not a fancy way of saying “just talk nicer to your kid.”

PCIT is an evidence-based therapy for kids aged 2–7 with, shall we say, “strong” personalities. It comes in two parts:

- Child-Directed Interaction (CDI): You follow their lead in play while giving precise praise for positive behaviour. Like sneaky Jedi training.

- Parent-Directed Interaction (PDI): You practise clear directions and consistent boundaries. Usually with a therapist coaching you to live.

And it works. Like, really works. Studies show large, lasting improvements in kids’ behaviour and in how calm and confident parents feel too (NCBI), (PMC).

For older kids? Meet PMT (Parent Management Training).

Usually for parents of kids (ages 5–12). Think of it as bootcamp for parenting brains. It teaches you how to:

- Reinforce good behaviours

- Use predictable consequences when rules are disrespected

- Set up clear routines

- Ignore the small mistakes that don’t need a fight

It’s more class-style than in-the-moment coaching. But it’s solid. Studies show PMT reduces problem behaviours and parental stress in a meaningful, research-backed way (ScienceDirect)

Big Changes, Big Feelings: Acting Out After Divorce, School, or New Sibling

Life pivots fast, and kids feel it all.

New school? New sibling? Family split? These shifts are enormous.

And your child’s reaction may be loud, odd, or completely regressive.

It’s not manipulation. It’s a flare for connection.

More rules won’t help. More presence will.

Stick to routines. Make space for one-on-one time. Be the calm in their storm.

5 Discipline Mistakes That Make Acting Out Worse

Let’s face it: when your kid’s losing it, it’s really tempting to go full drill sergeant. But some of our default reactions can accidentally fuel the fire instead of putting it out. Here are five common traps that actually make acting out worse:

Yelling

You feel like you’re asserting control, but your kid hears danger. Yelling activates their fight-or-flight response, not their listening skills.

Shaming

“What’s wrong with you?” or “Big boys don’t cry” might shut down the behaviour in the moment, but it builds guilt, not growth.

Empty Threats

“You’re never watching cartoons again.” (Sure, until tomorrow.)

If they don’t trust your word, they’ll test everything else too.

Ignoring Emotional Signals

Most behaviour is a message. If we ignore the signal, they’ll just turn up the volume.

Inconsistent Rules

Inconsistency confuses kids and makes them push harder to figure out what’s “real.”

Conclusion

Your child isn’t difficult by nature. He’s building himself in real time.

Loudly. Emotionally. Imperfectly.

Every outburst is a signal. Every meltdown, a moment to connect. Every misstep is a request for help in disguise.

So next time it happens, take a breath, drop your shoulders, and remind yourself: He’s not giving you a hard time. He’s having a hard time.

And you?

I bet you’re doing the best you can. And honestly? That’s what matters most.

TL;DR – What Dads Should Know About Acting Out

– Acting out = emotional expression, not bad behaviour

– Tantrums are short bursts; acting out is a pattern

– Impulsive behaviour is tied to brain development

– Persistent issues may need professional help

– Calm parenting works better than punishment

– PCIT and PMT are proven tools for change

– Connection matters more than perfection

References

Development of Impulse Control in Children: Neuroimaging Evidence

Executive Function and Brain Development in Early Childhood

The Structure of Temper Tantrums in Young Children

Diagnostic Criteria and Insights on Conduct and Oppositional Defiant Disorders

Temper Tantrums – Clinical Overview

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for Behavioural Problems

Parent Management Training Outcomes and Effectiveness

Frequently Asked Questions

Not at all. Acting out is a sign of a developing brain struggling with big feelings, not failed parenting. Your role isn’t to eliminate it, but to guide your child through it with calm, structure, and patience.

Because you’re their safe place. They hold it together elsewhere, then release the emotional load with you. It’s exhausting, but it’s also a deep sign of trust.

Not corrected, but shaped. Impulse control develops over time through brain growth, consistent modelling, and practice. Think repetition over reprimand.

Yes. But they should begin to decrease in frequency and intensity. If tantrums are frequent, extreme, or interfere with daily life, it’s worth checking in with a pediatrician.

When the behaviour becomes chronic, aggressive, destructive, or socially isolating, especially past age six, it could signal something deeper. Early support can make a real difference.

Start with your own breath. Name your emotion. Step away briefly if needed. You can’t co-regulate your child if you’re dysregulated yourself.

Grabbing toys, interrupting nonstop, hitting during play, blowing out someone else’s birthday candles, or running into the street without looking. All common signs of a brain learning control.

Most do, especially with support and steady parenting. But if left unchecked, those behaviours can become ingrained. Early, gentle guidance sets the foundation for long-term emotional regulation.